Time is brain. This phrase, coined by neurologist Camillo R. Gomez, MD in the early 1990’s and still used frequently today, underscores the urgency clinicians and care teams face in the rapidly evolving field of acute neurological care.

In the emergency department (ED), intensive care unit (ICU), and other acute care settings, no resource is more valuable than time—especially for patients with acute neurological conditions, where every second counts in detecting seizure. Left undiagnosed and untreated, seizures can lead to permanent brain injury, long-term disability, and even death. Yet non-convulsive seizures (NCS) and non-convulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) often go undetected —particularly in settings where conventional EEG is not readily available.

So how often does this really happen? The numbers tell a compelling story:

Even when EEG is available, delays in seizure detection are common in many acute care settings. One study found that only 3% of ED patients with suspected seizures or status epilepticus received EEG confirmation within 24 hours.v Clearly, there’s a gap between clinical need and diagnostic capability. What’s standing in the way?

Despite the critical need for EEG monitoring in emergency and intensive care units, conventional EEG can often fall short in meeting the demands of acute care. Common challenges include:

Common challenges include:

These limitations can significantly delay seizure detection and treatment, impacting patient outcomes in time-sensitive situations.

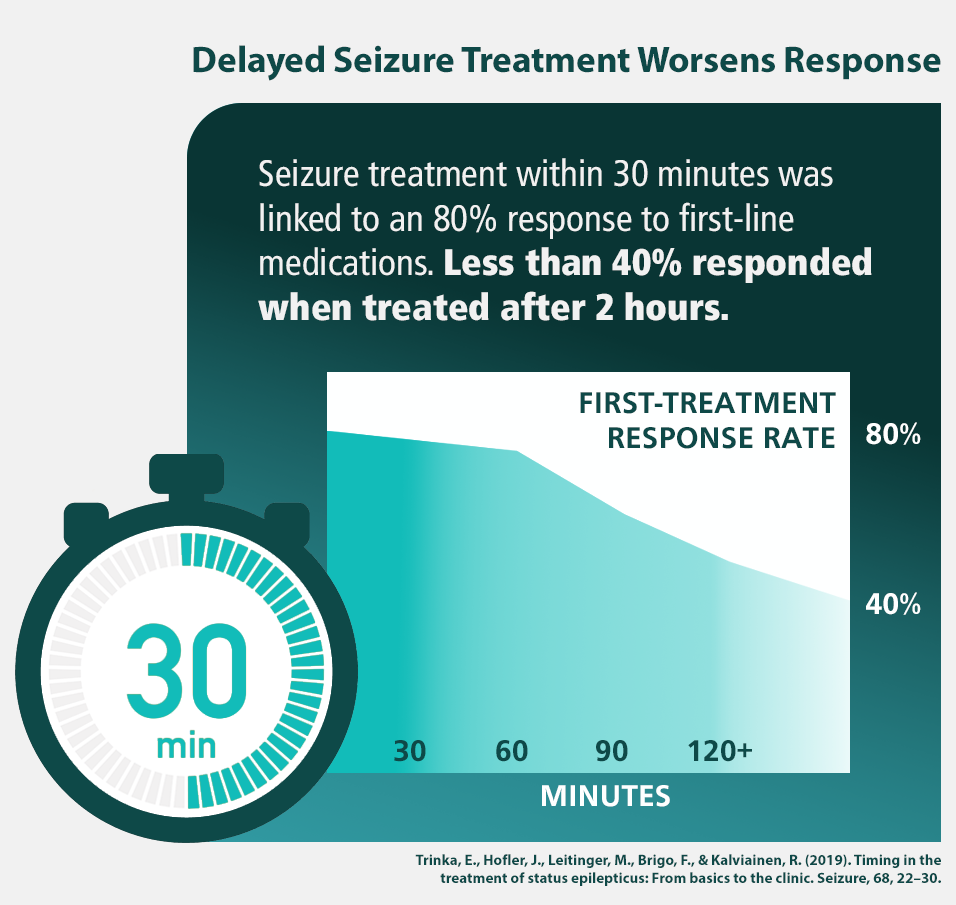

Sadly, many patients with suspected NCS and NCSE experience diagnosis delays that can be dangerous. In fact, research has pointed to a direct link between seizure duration and patient outcomes. A prolonged state of seizure activity often leads to higher mortality risk, irreversible brain damage, and a host of other negative impacts for critically ill patients.vi But what if there was a faster, more accessible way to diagnose seizures at the bedside? Enter Point-of-Care EEG.

For years, clinicians have recognized the need for a faster, more accessible solution for EEG monitoring. To bridge this gap, point-of-care EEG (POC-EEG)—also known as rapid EEG— is emerging as a transformative solution to help reduce the time to diagnose and treat patients with suspected NCS and NCSE.

Even early adopters are experiencing tremendous benefit from the new technology. In an observational study published in Emergency Medicine Journal, rapid EEG was rated as useful and/or diagnostic in 92% of patient cases.vii

ICU and ED clinicians and care teams report POC-EEG integrates effectively into acute care settings for several reasons:

New technology on the horizon provides even more benefit for acute care teams, neurologists and epileptologists. More advanced POC-EEG devices seamlessly integrate with neurology workflows, allowing for remote review by neurologists. This means specialists can analyze EEG results from anywhere, further accelerating treatment timelines.

The result? A smarter, faster, and more responsive approach to neurological care.

Advancements in technology make POC-EEG a game-changer for acute neuro care. Rapid EEG enables real-time screening, ensuring that non-convulsive seizures are diagnosed and treated more quickly. As a result, ED and ICU teams can deliver faster, more informed, and more effective care to patients with non-convulsive seizures and other serious neurological conditions.

POC-EEG not only helps to improve individual patient outcomes As acute care environments face increasing patient volumes and staffing shortages, technology that accelerates decision-making can make a critical difference—not just for the patient, but for providers as well.

Sources:

i. Westover, M. Brandon, et al. “The Probability of Seizures during EEG Monitoring in Critically Ill Adults.” Clinical Neurophysiology, vol. 126, no. 3, Mar. 2015, pp. 463–471, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2014.05.037.

ii. Zawar, Ifrah, et al. “Risk Factors That Predict Delayed Seizure Detection on Continuous Electroencephalogram (CEEG) in a Large Sample Size of Critically Ill Patients.” Epilepsia Open, vol. 7, no. 1, Mar. 2022, pp. 131–143, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34913615/, https://doi.org/10.1002/epi4.12572.

iii. Privitera MD, Strawsburg RH. Electroencephalographic monitoring in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1994 Nov;12(4):1089-100. PMID: 7956889.

iv. Lowenstein, D. H., and B. K. Alldredge. “Status Epilepticus at an Urban Public Hospital in the 1980s.” Neurology, vol. 43, no. 3, Part 1, 1 Mar. 1993, pp. 483–483, https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.43.3_part_1.483.

v. Kadambi P, Hart KW, Adeoye OM, Lindsell CJ, Knight WA 4th. Electroencephalography findings in patients presenting to the ED for evaluation of seizures. Am J Emerg Med. 2015 Jan;33(1):100-3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.10.041. Epub 2014 Oct 30. PMID: 25468214; PMCID: PMC4847441.

vi. Laccheo, I., Sonmezturk, H., Bhatt, A.B. et al. Non-convulsive Status Epilepticus and Non-convulsive Seizures in Neurological ICU Patients. Neurocrit Care 22, 202–211 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-014-0070-0

vii. Simma L, Bauder F, Schmitt-Mechelke T Feasibility and usefulness of rapid 2-channel-EEG-monitoring (point-of-care EEG) for acute CNS disorders in the paediatric emergency department: an observational study. Emergency Medicine Journal 2021;38:919-922.

048908 RevA